As part of UP42’s Partnership team, I speak to organizations looking to reach new markets and enable fascinating geospatial solutions to solve Earth’s challenges.

In my free time, my love of exploration has taken me to places like Everest Base Camp, Revillagigedo Archipelago, and last year when we were still able to travel; Antarctica.

The first time I heard that it was possible to visit Antarctica was when I watched the documentary by the genius filmmaker Werner Herzog, Encounters At the End of the World.

This idea stayed with me for years until last December 2019, when the dream became a reality and reality became a dream.

In this blog post, just over a year later, I’ll take you on my voyage to the end of the world through my experiences, photos, and learnings, as well as share why protecting the fragile region, is critical, now more than ever.

But first, since I took this trip 12 months ago, here are 12 quick facts about Antarctica:

- The word Antarctica comes from the Greek term “Antarktike”, meaning the opposite of Arctic or north.

- Antarctica is larger than Europe and almost double the size of Australia.

- The South Pole is found in Antarctica.

- Antarctica is considered a continent and is the southernmost continent on Earth.

- Most of Antarctica is covered by ice that is over 1.6 kilometers thick.

- Antarctica is surrounded by the Southern Ocean with a latitude of 60° S.

- There is no Aurora Borealis. In winter (March-September), there is an Aurora Australis or the Southern Lights.

- Antarctica is the windiest place on Earth, with wind speeds of over 350 kilometers per hour.

- Antarctica is the driest continent, with an icy desert and very little rainfall throughout the year.

- Around 90% of all ice on Earth is found in Antarctica. It is seasonally surrounded by up to 20,000,000 square kilometers (larger than Russia) of sea ice, which forms every winter and melts away to just 3,000,000 (roughly Argentina, mainly in the Weddell Sea) every summer

- Antarctica has one of the largest biomasses on Earth, with an estimated 100-500 million tonnes of krill in the Southern Ocean, which is why...

- 50% of all marine mammals live or are found passing through Antarctica

Fragile ecosystem

I knew I wanted to do something more than tourism when I visited the planet’s southern tip.

So, I reached out to Fraser Morgan, a researcher from the FOSS4G community__. He is Science Team Leader at Landcare Research—and I wanted to support his research on the impacts of human activities on the Antarctic environment.

A few weeks before my trip, I was in New Zealand for the FOSS4G Oceania Conference. There, it became apparent the kind of precautions in place to protect Antarctica’s fragile ecosystem. The immigration examinations ensure that no pests have been brought into the region.

Since those were pre-pandemic days, I had been traveling through Germany (where UP42 is based), New Zealand, Qatar, and Mexico (my home country) in the period of a month.

This raised an imminent biological alarm for the authorities in New Zealand, and I was quite rightly quizzed about where I, and the shoes I was wearing, had been.

Traveling responsibly is even more critical when visiting Antarctica since tourist boots can act as vectors for disease transmission—something we’re aware of now more than ever!

We were given authorized boots and had to go through a boot disinfection procedure every time we disembarked or boarded our vessel.

Setting sail

It has to be said, it’s not very easy to get to Antarctica. In my case, my vessel departed from Ushuaia and took 2 days to cross the Drake Passage—one of the most tumultuous bodies of water in the world.

I took screenshots of my location during the journey using OpenStreetMap as a basemap to capture our voyage across the Drake Passage

I took screenshots of my location during the journey using OpenStreetMap as a basemap to capture our voyage across the Drake Passage

This rough ride is because currents meet from several different oceans, such as the Pacific, Atlantic, and Southern, as well as the Cape Horn currents.

When crossing the Drake Passage, the legend goes that the kind of turbulence you face depends on Drake’s mood. I was told that we would either face Drake’s ‘shake’ or Drake’s ‘lake.’

I most definitely experienced Drake’s shake! After ten hours in a medium intensity storm, seeing chairs and water bottles flying around my cabin, I realized how rough sailing in a strong storm could be!

Our vessel was the Ortelius, named after the first modern atlas’ creator, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum in 1570.

It is a class UL1 icebreaker vessel and can navigate in solid one year sea ice and loose multi-year pack ice.

I’ve created 3D photos of the journey using Mapillary which you’re able to view here, here, and here.

In Antarctica

Upon arrival, after waiting for so long and weathering Drake’s shake, the calm ocean was a welcome surprise—as were the wildlife that welcomed us! We spotted fin whales, orcas, and humpback whales.

In the days that followed, we also saw Wendell seals, gentoo penguins, chinstrap and Adélie penguins, minke whales, and had a close encounter with a Leopard Seal.

We were able to disembark at assigned spots in the Antarctic peninsula.

I soon became accustomed to the kind of procedures for cleaning and disinfecting, to avoid introducing any foreign species to the pristine environment.

The rules were clear: we were to take nothing but photographs and memories and leave nothing behind.

We also were instructed to not be any closer than 5 meters if we encountered any Antarctic wildlife such as curious penguins or seals.

Part of my trip’s objective was to support with some data collection for Fraser’s research on the impact of people in Antarctica.

Unfortunately, before leaving Germany, the GPS devices didn’t make it on time from New Zealand. But, while I was unable to use Fraser’s GPS devices, I did collect a few GPS tracks with my phone and Lat/Long coordinates of the vessel trip logs.

The scientists in the project have been collecting more than 15 years of human activity data to study where people in Antarctica go and it’s impact.

Human activities, particularly construction and transport, have led to disturbances of Antarctic flora and fauna. For example, a small number of non-indigenous plant and animal species has become established in the area.

In the face of the continued expansion of human activities in Antarctica, human activity research aims to implement measures that protect the Antarctic environment—including its intrinsic wilderness and scientific values.

By measuring and assessing human impact at various spatial and temporal scales, researchers can identify the effect and, through a sample collection—determine how pristine the area is.

Why is Antarctica so important for Earth?

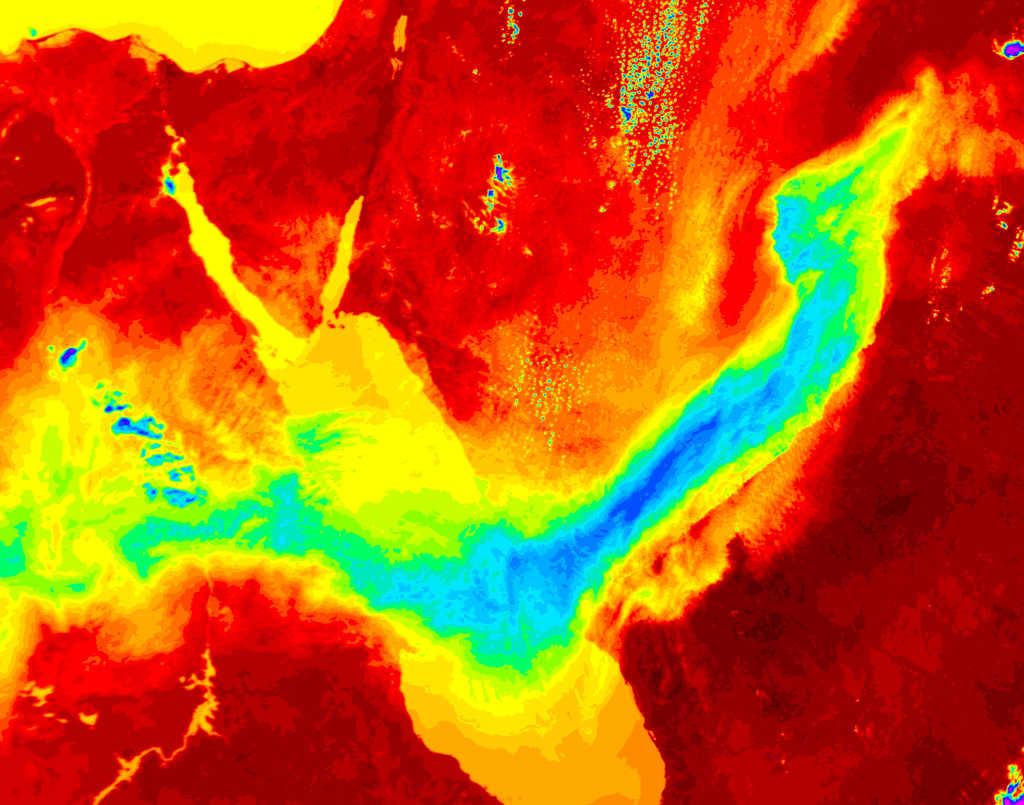

Antarctica has a significant role in the Earth’s heat balance.

Ice is reflective, whereas land and water tend to absorb light and increase temperatures. The massive Antarctic ice sheet reflects a large amount of solar radiation away from the Earth’s surface.

When sheets and glaciers melt and disappear, the reflectivity of the Earth’s surface also decreases.

This means more incoming solar radiation is absorbed by the Earth’s surface, causing the ice to melt and sea levels to rise.

We already know what can happen next and are now facing the reality of dramatic changes in our environment.

What we have been witnessing in Australia, California, and so many other regions, unfortunately, makes it clear that we humans are reacting to the climate crisis very late.

I was prepared for dramatically low temperatures due to the changing climate. However, I was surprised to have had one day that was 17° C. This is something for us to be very worried about.

In Antarctica, we can find over 50% of all marine mammals in the world. However, some of them have almost become extinct after whaling began on a large scale in the early 20 Century.

How can research and Earth observation data support Antarctica?

Researching Antarctica

Until September 2018, we had a more detailed map of Mars than we did of Antarctica.

There is so much to discover about the white continent.

Research in multiple fields is taking place, such as studies from scientists in the FOSS4G community, including the scientist I supported, Fraser Morgan, who evaluates human impact in the area.

Alongside Fraser, the team at the Norweigan Polar Institute, has developed Quantarctica, a collection of geographical datasets that include community-contributed, peer-reviewed data from ten different scientific themes. Initiated and maintained by Kenichi Matsuoka, Quantarctica is a useful tool for the research community, classrooms, and for operational use in Antarctica. It contains Antarctic datasets such as base maps, satellite imagery, glaciology, and geophysics data from around the world, prepared for viewing in QGIS.

Antarctic Data Analysis, or ADA, helps to provide the context to assist the Antarctic policy community without the need for GIS expertise.

A research project by Dr. Adam Steer, helped to estimate sea-ice thickness at the meter-scale, using airborne Lidar and tools for one-ground measurements. These help us understand detailed physical and ecological systems in sea-ice, and interpret satellite observations.

Now, he is researching Arctic sea ice as part of his post-doctorate at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

The current pandemic has not stopped polar science. There are many other kinds of research underway, beyond geographic and oceanographic disciplines, including marine biology.

Marine Scientist Pippa Low specializes in marine mammals and leads the efforts to build the first Southern Ocean-wide photo ID catalog for Leopard Seals.

She applies citizen science technologies developed by Happy Whale to identify and protect whales, to do the same for Leopard Seals.

This beautiful and “smiley” creature is one of the top Antarctic predators and the least known. There is still so much to be discovered!

Using Earth observation satellites

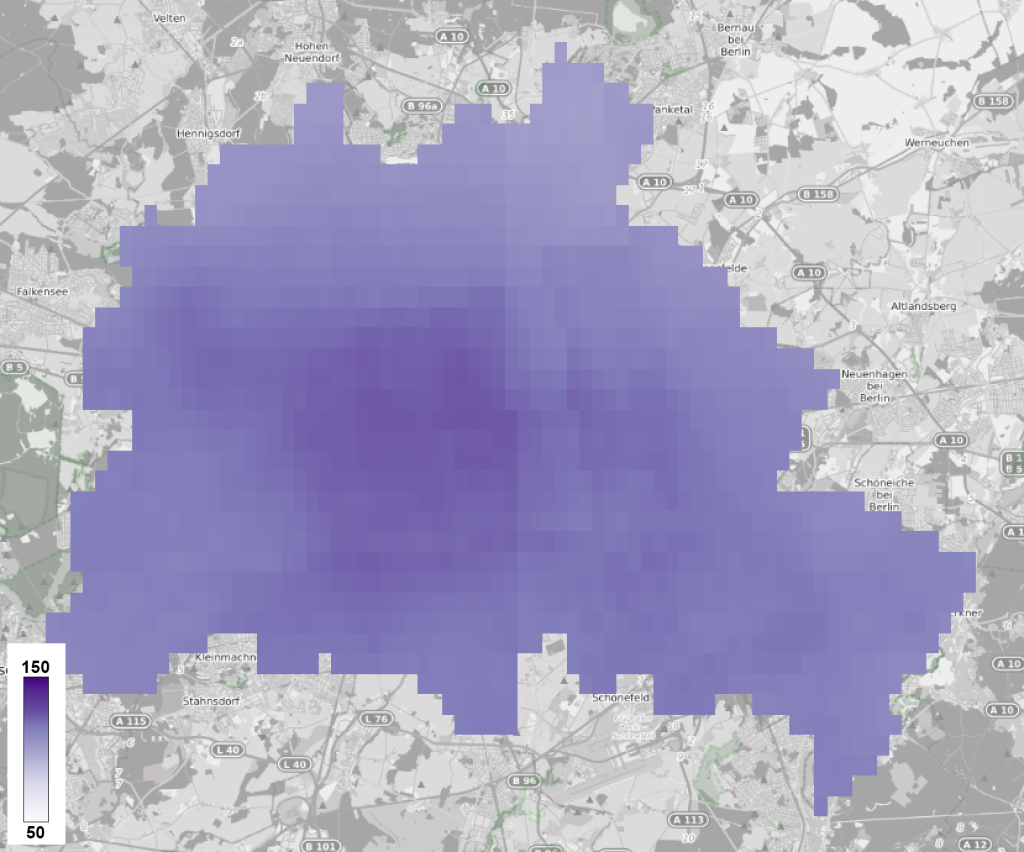

At UP42, we are creating the largest geospatial marketplace and platform in one—where you can combine multiple datasets with third party algorithms.

We offer Earth observation (EO) satellite data from the Copernicus Programme constellations such as Sentinel 1, 2, 3, and 5P, as well as supporting algorithms for polar regions, oceans, maritime, forestry, coastal management, climate change, and more.

On our blog, we cover data stories where you can find examples of how we help to solve these challenges.

Every day, we are speaking with and welcoming new partners who bring valuable geospatial products on board.

To continue growing the UP42 marketplace, we are always on the lookout for people creating data and analytics tools to partner with us, including those that can support research in various regions of the globe, especially the areas facing more risk, such as the polar regions.

Please get in touch with me to bring yours to UP42.

Another exciting new satellite that will be able to support with research is Sentinel-6.

Recently launched on 21 November 2020, the new Copernicus satellite will monitor sea-level rise through high precision ocean altimetry measurements. Sentinel-6 will continue important sea-surface research and measure 95% of the ice-free sea levels every ten days until at least 2030.

The satellite will be joined by its twin, Sentinel-6B, in 2025, and together, they will make up the Sentinel-6/Jason-CS mission.

With the global mean sea level rising, this kind of EO data is crucial to monitoring changes worldwide, but especially in our vulnerable polar and coastal region.

Over 680 million people live in coastal areas less than 10 meters above sea level–this is expected to increase to a billion by 2050.

The future of Antarctica

Thanks to the Antarctic Treaty from 1961, currently signed by 53 countries, Antarctica is officially designated as “a natural reserve devoted to peace and science”.

In 2016, the Ross Sea became the largest marine protected area with 1.57m sq km of the Southern Ocean, gaining commercial fishing protection for 35 years.

This is very positive, but we still need to figure out how to mitigate or reverse the melting icebergs and ice-sheets—which are currently ongoing and will have disastrous effects for life on Earth.

Last October, the Polarstern vessel arrived at Bremerhaven port carrying more than 150 Terabytes of data after one year drifting in the arctic region. The MOSAiC Expedition (Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate) is the largest arctic science expedition so far in history.

The mission leader, Markus Rex, summarized what the researchers found "we witnessed how the Arctic ocean is dying".

Antarctica is the last place on the planet where we can still find nature in its most pristine state of beauty.

Even one year later, it is hard for me to believe that I traveled the same route as explorers, adventurers, as well as, unfortunately, problematic whalers and sealers.

For now, as the world undergoes a rapid change in more ways than ever, I hope this look back at my Antarctic dream gives you a glimpse into the past and inspires you to protect the future.